As of now, we can create a new post and we can show one hard-coded post. It’s almost time to add some structure and navigation to our app. Let’s show a list of posts first, though, and we can think about how we navigate between items later.

Let’s add a list component to show all the posts. We’ll fake it in the front end…

export function Main() {

return <div id='main'>

<Editor onSubmit={create} />

<List />

</div>

}

// /javascript/posts/List.jsx

export default class List extends React.Component {

render() {

return 'list of posts'

}

}

… until we have the backend in place.

The posts.index action in PostsController will return the React application if you request HTML and a list of posts if you request JSON.

# PostsControllerTest.rb test 'the index page just returns the react application' do get posts_url assert_select '#react' end test 'fetch a list of posts as json' do get posts_url(format: :json) assert_response :success json = JSON.parse response.body, symbolize_names: true assert 1, json[:posts].count assert 'The title', json[:posts][0][:title] end

# PostsController.rb

def index

@posts = Post.all.order(created_at: :desc)

end

# index.json.jbuilder

json.posts do

json.array! @posts do |post|

json.extract! post, :id, :title, :body, :created_at, :updated_at

end

end

And, if I open http://blogging.local:3000/posts.json in the browser, I see my posts. Now to fetch them from the client.

I’ll add an API methods to fetch the list of posts…

// posts/api.js

export function list() {

return server.get(`/posts.json`)

}

…and update the List component to call it and render the list.

export default class List extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props)

this.state = {

posts: null

}

}

render() {

const {posts} = this.state

if(posts === null) return 'Loading…'

return <ul className='posts-list'>

{

posts.map(post => <li key={post.id}>

<Post post={post}/>

</li>)

}

</ul>

}

async componentDidMount() {

const response = await list()

this.setState({posts: response.posts})

}

}

That’s all straightforward, I think, except: note the key property in <li key={post.id}>.

React performs optimisations by keeping track of changes to the React component tree and only re-rendering components that have changed since the last render. When you render an array of components you should provide a unique key to each component to help React figure out what has changed.

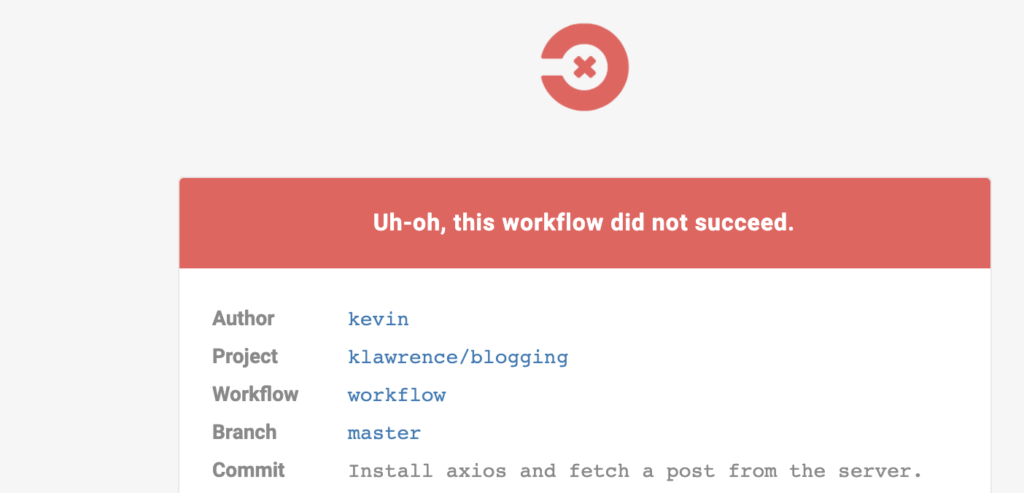

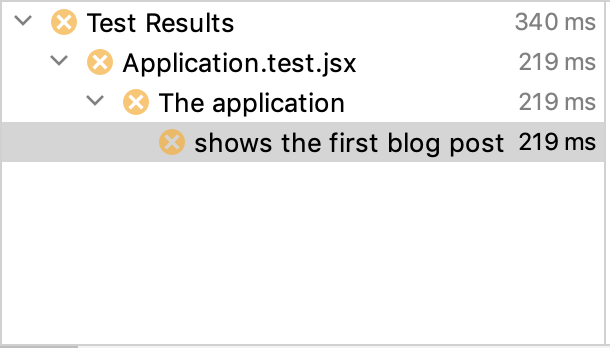

If I run all the Javascript tests now, I see a failure in the top-level Application.test.jsx because it is still expecting a single Post component rather than a list.

Let’s fix that.

// Application.test.jsx

describe('The application', () => {

server.send = jest.fn()

const post = {

id: 1,

title: 'React on Rails',

body: 'I can use React with Rails.',

}

const posts = [post]

beforeEach( () => {

// Return a list of posts instead of a single post

server.send.mockReturnValue({posts})

})

test('shows a list of blog posts', async () => {

const component = await display(<Application />)

component.update()

assert_select(component, '.site-name', 'Blogging')

assert_select(component, '.post .title', 'React on Rails')

assert_select(component, '.post .body', 'I can use React with Rails.')

expect(server.send).toBeCalledWith('/posts.json')

})

})

I’m not sure why, but I had to add component.update() to get the list component to render the correct HTML (I think this might be a bug in Enzyme).

I like to think of the top-level Application.test as a kind of smoke test that tests the whole application from end to end, albeit in a rather shallow fashion. It won’t tell us anything profound about the application’s behaviour but it might flag some future regression that would be missed by lower-level unit tests.

As I did with the Post.test, I’ll duplicate this test as a unit test so I can test the List component more thoroughly. But first I am going to split the component into a List that knows how to render a list of posts and a ConnectedList that knows how to fetch a list of posts from the server.

This seems like a lot of faff when I am typing it into WordPress but it’s literally 10 seconds of copy-paste in the IDE and my future self will thank me when I need to write more complex tests and I can do so without loading the whole framework.

Here’s the code.

// posts/List.jsx

export function List({posts}) {

return <ul className='posts-list'>

{

posts.map(post => <li key={post.id}>

<Post post={post}/>

</li>)

}

</ul>

}

export default class ConnectedList extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props)

this.state = {

posts: null

}

}

render() {

const {posts} = this.state

if(posts === null) return 'Loading…'

return <List posts={posts} />

}

async componentDidMount() {

const response = await list()

this.setState({posts: response.posts})

}

}

And here are the tests: one for the List and one for the ConnectedList.

// posts/List.test.jsx

describe('The post list', () => {

server.send = jest.fn()

const post = {

id: 1,

title: 'React on Rails',

body: 'I can use React with Rails.',

}

const posts = [post]

test('shows a list of blog posts', () => {

const component = display(<List posts={posts}/>)

assert_select(component, '.posts-list .post', 1)

assert_select(component, '.post .title', 'React on Rails')

assert_select(component, '.post .body', 'I can use React with Rails.')

})

test('fetches the list of blog posts from the server', async () => {

server.send.mockReturnValue({posts})

const component = await display(<ConnectedList />)

component.update()

assert_select(component, '.posts-list .post', 1)

expect(server.send).toBeCalledWith('/posts.json')

})

})

A quick test in the browser shows that I can show a list of posts from the server and I can create a new one except… Ooops!… the new one doesn’t get added to the list unless I refresh the page.

This is the kind of problem that Redux will solve for us but I have a different approach in mind. We’ll give it a try in the next episode.