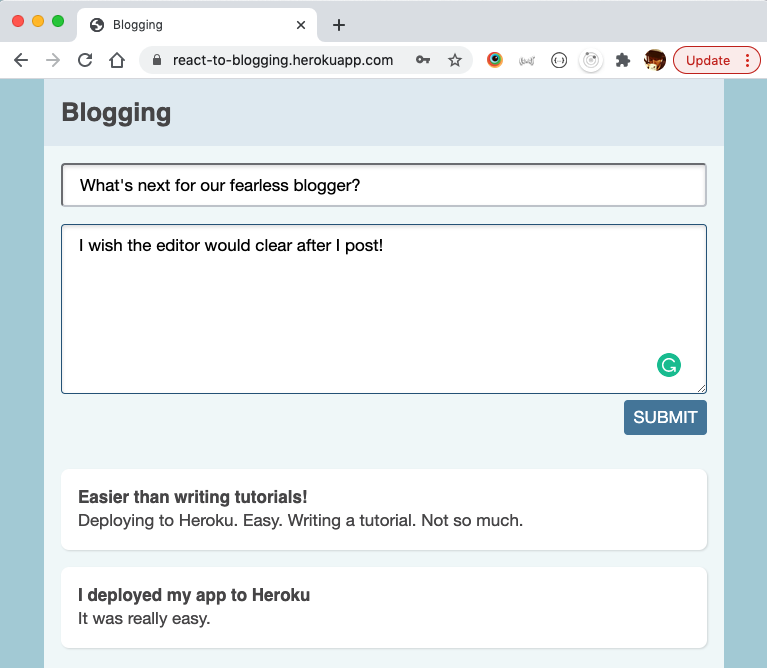

The next story wants us to let authors edit their own posts but we don’t have an association between posts and users yet.

- An author can edit a blog post.

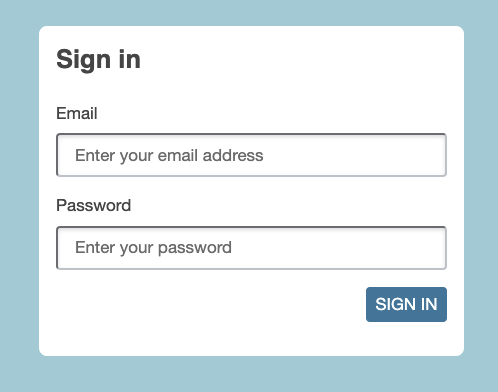

We don’t have a way to create users either, except in the Rails console.

Normally, we’d scaffold a UI in Rails, but I want to do this in React to see how the Store that we created for posts generalises to other models and associations.

I’ll start by adding some missing details to the user model.

# rails g migration AddNameToUser name:string

class AddNameToUser < ActiveRecord::Migration[6.1]

def change

add_column :users, :name, :string

add_column :users, :role, :integer

add_index :users, :name, unique: true

end

end

# User.rb

class User < ApplicationRecord

authenticates_with_sorcery!

enum role: [:guest, :author, :admin]

validates :name,

presence: true,

uniqueness: true,

length: { minimum: 2, maximum: 20},

format: /\A[a-z_][\sa-z0-9_.-]+\z/i

validates :email,

presence: true,

uniqueness: true,

format: /\A[^@]+@[^@]+\.[^@]+\z/i

end

Now I’ll add a UsersController to return some JSON to the client. The tests are on GitHub.

# routes.rb Rails.application.routes.draw do root to: 'posts#index' resources :posts resources :sessions resources :users get :sign_in, to: 'sessions#new', as: :sign_in end

class UsersController < ApplicationController

skip_before_action :require_login, only: :show

before_action :require_admin, except: :show

before_action :set_user, except: :index

helper_method :current_user, :admin?

def index

@users = User.by_name

end

def show

end

protected

def set_user

@user = User.find params[:id]

end

def admin?

current_user&.admin?

end

def require_admin

require_login

raise Errors::AccessError unless admin?

end

end

# app/lib/errors/access_error.rb class Errors::AccessError < StandardError

-# views/users/index.json.jbuilder json.users do json.partial! 'users/user', collection: @users, as: :user end

-# views/users/show.json.jbuilder json.partial! 'users/user', user: @user

-# views/users/_user.json.jbuilder if admin? json.extract! user, :id, :name, :email, :role, :created_at, :updated_at else json.extract! user, :id, :name end

Now, after a bit of tidying, we have an AccessControl concern…

# app/controllerrs/concerns/access_control.rb

module AccessControl

extend ActiveSupport::Concern

included do

before_action :require_login

helper_method :current_user, :admin?

end

protected

def admin?

current_user&.admin?

end

def require_admin

require_login

raise Errors::AccessError unless admin?

end

end

…that gets loaded by the ApplicationController and the UsersController simplifies to this:

class UsersController < ApplicationController

skip_before_action :require_login, only: :show

before_action :require_admin, except: :show

before_action :set_user, except: :index

layout 'react'

def index

@users = User.by_name

end

def show

end

protected

def set_user

@user = User.find params[:id]

end

end

I also extracted a layout file for the react container so I don’t have to repeat it for every view that needs it.

<% content_for :body do %> <div id='react' data-user-id='<%= current_user&.id%>' /> <% end %> <%= render template: 'layouts/application' %>

And now for the bit that I am most interested in. I want to make it as easy to create a React app — for the CRUD actions at least — as it is to do with Rails views.

Let’s look at the Store that we created for posts.

export class Store {

constructor() {

this.all = []

this.by_id = {}

this.subscribers = []

}

async list() {

const {posts} = await list()

this.addAndNotify(posts)

return posts

}

async find(id) {

let post = this.by_id[id]

if(! post) {

post = await fetch(id)

this.addAndNotify(post)

}

return post

}

async create(post) {

post = await create(post)

// todo don't add it to the store unless it is valid

this.addAndNotify(post)

return post

}

addAndNotify(post_or_posts) {

if(Array.isArray(post_or_posts))

post_or_posts.forEach(post => this.add(post))

else

this.add(post_or_posts)

this.all = Object.values(this.by_id).sort(by_created_at)

this.notify()

}

add(post) {

this.by_id[post.id] = post

}

// extract this to a class

subscribe(fn) {

this.subscribers.push(fn)

}

unsubscribe(fn) {

this.subscribers = this.subscribers.filter(subscriber => subscriber !== fn)

}

notify() {

// do a dispatch thing here with a queue

this.subscribers.forEach(fn => fn())

}

}

export const store = new Store()

There’s nothing about that that is specific to posts. It should work for any model so let’s extract the beginning of a library for binding the React UI to the Rails API with minimal coding.

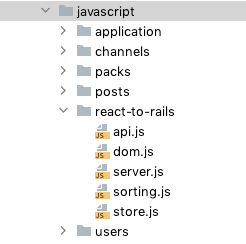

I moved the Store to the new directory that will be the start of our library and parameterised the constructor to take a type.

// ReactToRails/store.js

export default class Store {

constructor(type) {

this.type = type

this.plural = pluralize(type)

this.all = []

this.by_id = {}

this.subscribers = []

}

// ...

I moved everything into this directory that is not part of the Blogging domain: api.js; sorting.js; server.js. Everything.

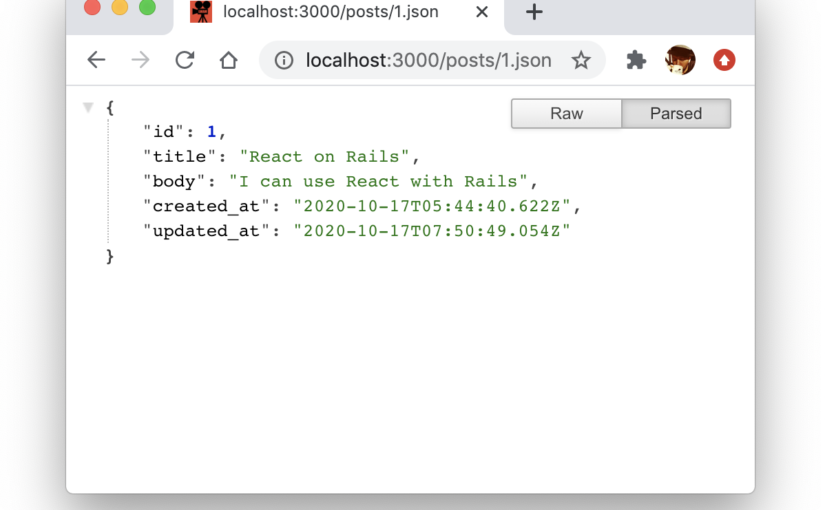

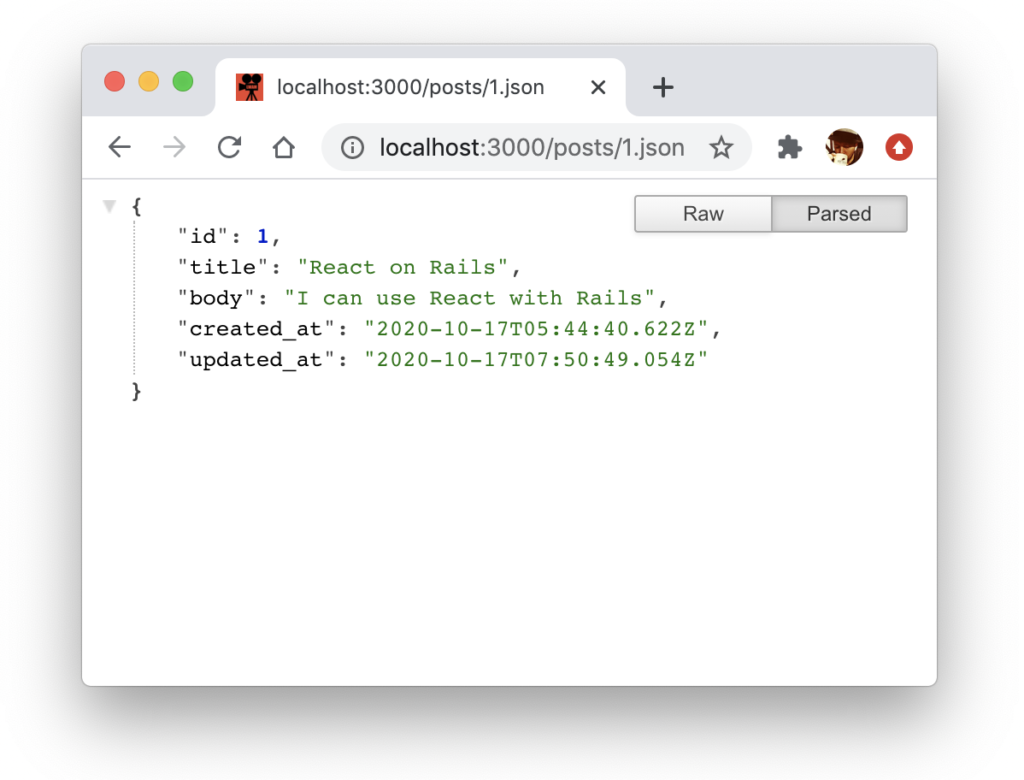

I parameterised the api calls to take a type. It uses the simple rule that URLs take the form /plural-of-type.json which covers the majority of URLs. When we get one that doesn’t follow this rule, we’ll do something more sophisticated.

export function fetch(type, id) {

return server.get(pathToShow(type, id))

}

export function list(type) {

return server.get(pathToIndex(type))

}

export function create(type, record) {

return server.post(pathToIndex(type), {[type]: record})

}

function pathToShow(type, id) {

return `/${pluralize(type)}/${id}.json`

}

function pathToIndex(type) {

return `/${pluralize(type)}.json`

}

export function pluralize(type) {

return `${type}s`

}

Let’s look at those ConnectedXXX components next.

// posts/List.jsx

export default class ConnectedList extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props)

this.store = this.props.store || store

this.state = {

posts: null

}

this.storeDidUpdate = this.storeDidUpdate.bind(this)

}

render() {

const {posts} = this.state

if(posts === null) return 'Loading…'

return <List posts={posts} />

}

async componentDidMount() {

const posts = await this.store.list()

this.setState({posts})

this.store.subscribe(this.storeDidUpdate)

}

componentWillUnmount() {

this.store.unsubscribe(this.storeDidUpdate)

}

storeDidUpdate() {

const posts = this.store.all

this.setState({posts})

}

}

That’s 98% boilerplate and we can extract that away to the library too. Let’s try a higher-order component (HOC) the way that Redux does for connected components.

According to the React site,

a higher-order component is a function that takes a component and returns a new component.

We are going to use it for two things:

- To parameterize the ConnectedList.

- To connect the list to the store.

Here it is:

// ReactToRails/ConnectedList.jsx

export function connectList(WrappedList, store) {

return class extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props)

this.state = {

records: null

}

this.storeDidUpdate = this.storeDidUpdate.bind(this)

}

render() {

const {records} = this.state

if (records === null) return 'Loading…'

const props = {

[store.plural]: records

}

return <WrappedList {...props} />

}

async componentDidMount() {

const records = await store.list()

this.setState({records})

store.subscribe(this.storeDidUpdate)

}

componentWillUnmount() {

store.unsubscribe(this.storeDidUpdate)

}

storeDidUpdate() {

const records = store.all

this.setState({records})

}

}

}

It’s functionally equivalent to the ConnectedList we had before, but this one lets us pass in a store object and a List component. and it doesn’t care about the types.

Here’s what it does:

- Fetch a list of records from the store.

- Subscribe to updates from the store.

- Updated the WrappedList when the records are added to the store.

We can call from list.jsx.

// posts/list.jsx export default connectList(List, store)

We can do the same de-boilerplating for the ConnectedPost component.

// ReactToRails/ConnectedView.jsx

export function connectView(WrappedView, store) {

return class extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props)

this.store = this.props.store || store

this.state = {

record: {}

}

}

render() {

const {record} = this.state

const props = {

[this.store.type]: record

}

return <WrappedView {...props} />

}

async componentDidMount() {

const record = await this.store.find(this.props.id)

this.setState({record})

}

}

}

export default connectView(Post, store)

All the boilerplate is gone from our App now and, with any luck, it should be easy to add the crud pages for users.